A commodity is a strange thing

A commodity appears at first sight an extremely obvious, trivial thing. But its analysis brings out that it is a very strange thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties. So far as it is a use-value, there is nothing mysterious about it, whether we consider it from the point of view that by its properties it satisfies human needs, or that it first takes on these properties as the product of human labour. It is absolutely clear that, by his activity, man changes the forms of the materials of nature in such a way as to make them useful to him. The form of wood, for instance, is altered if a table is made out of it. Nevertheless the table continues to be wood, an ordinary, sensuous thing. But as soon as it emerges as a commodity, it changes into a thing which transcends sensuousness. It not only stands with its feet on the ground, but, in relation to all other commodities, it stands on, its head, and evolves out of its wooden brain grotesque ideas, far more wonderful than if it were to begin dancing of its own free will — Karl Marx[1]

In ‘The Fetishism of Commodities and the Secret Thereof’, the final section of the first chapter of Capital, Marx makes a sardonic reference to ‘table-turning’, a fashionable Victorian pastime that flourished in England alongside the Spiritualist wave imported from America in 1852–53. A kind of séance, participants would sit around a table, their hands resting upon its top, awaiting spontaneous rotations, tilts or levitations that were understood to be communications from the dead.

That the most humble and utilitarian of objects could carry so much mystical import, Marx found absurd, but not so fantastical as the means by which a product of labour is turned into a commodity. When exchange-value takes precedence over use-value, social relations between people are transformed into social relations between things. With its labour processes obscured, the table is animated and becomes something other than a surface for eating, writing, or working at. In sum, there is a conflict between form and content. Marx implemented the concept of the fetish for its evocation of transcendence from the material. He borrowed the term from proto-anthropologist Charles de Brosses, who in his 1760 publication The Cult of Fetish Gods defined the fetish as an inanimate object bestowed with otherworldly powers, a feature of the so-called ‘primitive religions’.[2]

How has this dynamic advanced since Marx’s analysis? The dematerialisation of the commodity has only further detached the product from its constituent labour relations. The development of financial capitalism including speculative trading, the knowledge economy, and digitalisation are some of the processes that are contributing to this increased gap. The space between commodity and labour continues to generate the magical, the strange and the ineffable, but in ways that increasingly abstract, in accordance with newer capitalist modes.

David Attwood combines an anti-fatigue mat and a pair of Classic Crush Clog Crocs, accoutrements of the serious knowledge-worker, in Anti Fatigue II (2023). Both items have their origins in manual forms of labour, being used for their practical functions in hospitality work, healthcare settings, and boating (in the case of Crocs), and promise to counteract the bodily impacts of these activities. In their adoption by white-collar employees, their associations have been reassigned to immaterial labour. In 2022, Crocs reported a record-high revenue of $3.6 billion, almost a 54% increase from the previous year. This surge in popularity has been connected with a desire for comfort and functionalism following the move to working from home during the pandemic. They now occupy the realm of high fashion, with collaborations between the footwear brand and luxury house Balenciaga selling out before their release date. The magic of both products lies in the elevation of utilitarian qualities – comfort, endurance and ergonomic efficiency – to make them desirable to a middle-class (as well as upscale) consumer.

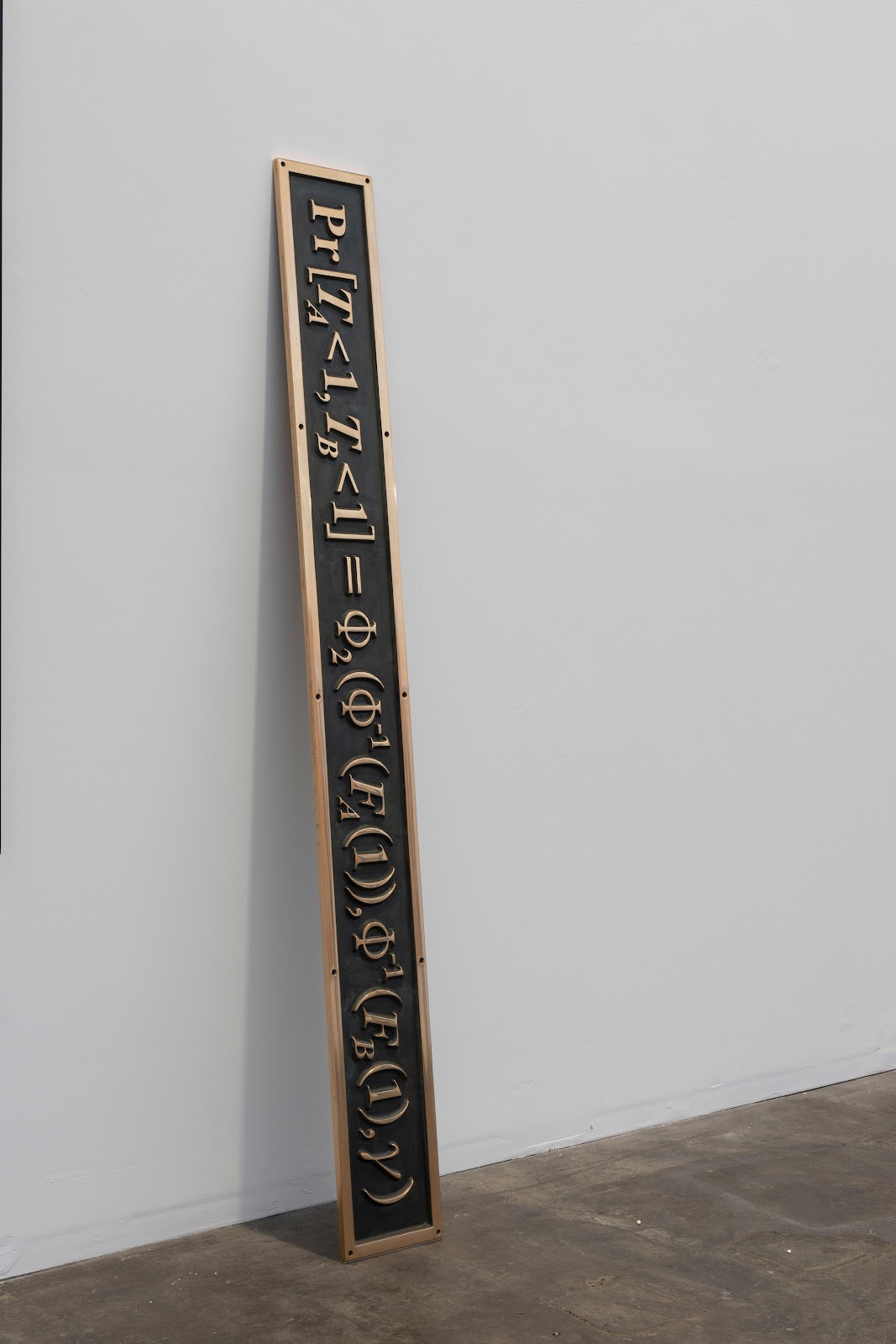

In his sculptural work I’ll Be Gone, You’ll Be Gone (2013–14), Daniel McKewen gives physical form to a mathematical model – quantitative analyst David X. Li’s Gaussian copula – that was sharply criticised for its supposed role in the 2007–08 Global Financial Crisis. The equation was published by Li in a 2000 research paper, and quickly taken up by banks and investors to price and manage the risk of Collatarised Debt Obligations (CDOs) (complex structured financial products backed up by a pool of debts, including mortgages) with greater ease, and at a remarkably faster pace. Despite early indications of weaknesses in the model, including its reliance on correlation, its implementation went unhindered. McKewen points to the oracular role of the ‘quant’, a figure couched in associations with rationality and logic, but who in reality, is equally led by interpretation and intuition. These highly specialised individuals prophesise through elegant algorithms, decipherable to an exceptional few, making decisions based on volatile market movements. Their statistical methods and economic theories form an occult cosmology far removed from the reality of the material commodity. In solidifying Li’s copula, the artist highlights this irony, and makes the mathematical model into a fetish proper.

Darren Sylvester’s Fortune Teller (2019) captures the moment of monetary exchange between clairvoyant and client, the act that must necessarily close every rendering of service, spiritual or otherwise. The photograph crystallises a fundamental move in the transformation of a product into a commodity – the quantification of value through the money form – largely unseen in an age of contactless payment. We might also understand the ‘hard cash’ itself as the content of the service provided, with capitalism now functioning as a source of meaning and identity for the consumer-subjects of the over-developed world. In 1921, philosopher Walter Benjamin described capitalism as a religion, claiming it ‘allay[ed] the same anxieties, torments, and disturbances to which the so-called religions offered answers’[3] in preceding eras. The lithe, manicured hand is cast in a sickly, unnatural green hue, and disembodied from any figure. Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’, the famous metaphor for the unseen forces driving the free market, comes to mind.[4] Both alluring and powerful, this hand is an unearthly authority, exercising its will according to its own mysterious whims, and as such should be regarded with a fearful reverence.

In the instant that a product of labour assumes the form of a commodity, something strange happens.

— Stephanie Berlangieri

[1] Marx, Karl, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume 1, Penguin, 1976, pp. 163–64.

[2] de Brosses, Charles, Du culte des dieux fétiches, Fayard, 1988.

[3] Benjamin, Walter, Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings. Volume 1: 1913–1926, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1996, p. 288.

[4] Smith, Adam, The Wealth of Nations, Dent, 1977.