Jonathan Ehrenberg

The Capital of Fine is OK

July 1-30, 2022

Essex Flowers

19 Monroe Street, NY, NY 10002

|

Interior, clay and mixed media on panel 24 x 18 x 8 inches, 2022 |

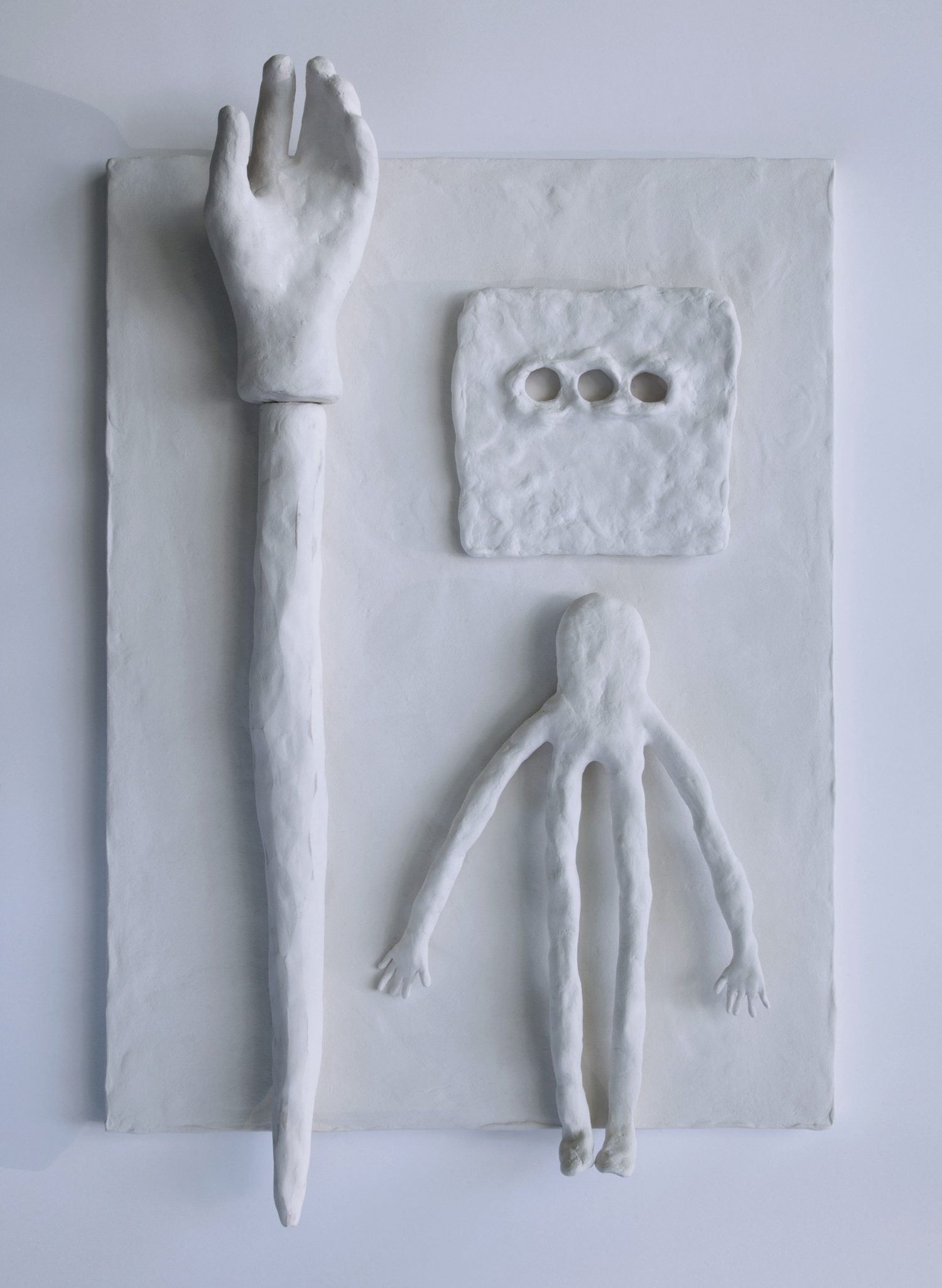

Jonathan Ehrenberg’s new reliefs are handmade riffs on his digital output that explore how changes in the body affect the mind. In their post-digital afterlife, mouths and other parts begin to eat themselves, dispersing the body among its own perceptions. Jonathan currently has a solo show of these new reliefs at Essex Flowers. The exhibition’s title “The Capital of Fine is OK” is borrowed from his three-year-old daughter, Mia, who has a curious obsession with geography. One day she was rattling off countries and capitals—The capital of France is Paris. The capital of China is Beijing—when she got a big idea: The capital of Fine is OK! As the artist watched language form the intuitive, arbitrary, oddly associative building blocks of his daughter’s expanding reality, he also saw his father’s world focus in on bodily concerns: arthritic joints, a deteriorating hip. His new series of wall reliefs similarly mines the rattle-bag of the unconscious as it pieces the world together and segments the self into parts. *

|

Medium, clay and mixed media on panel 29 x 18 x 3 inches, 2022 |

Irini Miga: “The Capital of Fine is OK” – what a brilliant title for a show. It is immediate and it marks the importance that associations play in your practice. Your work is a micro-cosmos that connects family lineage with your own artistry and the unknown. You have mentioned Solaris to me. So: “Let us take you with us to Solaris, planet of mystery, embodiment of man's latent conflict with the unknown. Man, face to face with his conscience, and with his past.” What does hybridity mean to you and your work, and how references come into being?

Jonathan Ehrenberg: That’s quite a question! My daughter, who’s 3, is obsessed with the capitals of countries, and she came up with that line. It got me thinking about her understanding of capitals, and countries, and physical places in general. Did she understand these concepts? What was she visualizing as she said these words? I watch her make new connections every day and I have a parent’s intuition for what they might be, but she’s still very much a black box.

I mentioned to you earlier that there are images in Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris that I keep thinking about. In the novel, the planet Solaris’s sentient ocean generates simulacra of its visitors’ inner worlds from its own pink foamy material. A pilot flies over the ocean, and the ocean forms a giant version of his baby (at least that’s how I remember it), but it doesn’t understand the baby from a human point of view. It doesn’t tell itself stories about objects the way humans do, so it gets things wrong, puts things in the wrong place with no understanding of how the object functions and how its parts fit together.

I’ve been making a lot of work on the computer over the last few years, and this “alien” understanding of our most familiar objects feels very much like how a computer processes information. The computer has a powerful aesthetic that notably lacks human intentionality, that tells no stories about the forms it generates, like Solaris, from one endlessly fluid and adaptable material.

The work in this show also has a very consistent physical quality. I like the idea that the pieces in the show are like a snapshot of a person building internal forms and in-the-process of finding language for things in the world.

|

Speech, clay and mixed media on panel 24 x 22 x 7 inches, 2022 |

I M: The work in your solo show is beautiful and arresting. It feels serene and at the same time unsettlingly aggressive. I feel like you are building with your own personal Lego-blocks a world that is at once intimate and peculiarly familiar. Is the language of art a universal language of conceiving the world or alternatively through the language of art we comprehend the world?

J E: Thanks Irini. I think our perceptions of the world are formed by things peculiar to each of us—the wiring we’re born with, and the connections and associations we form through the things that happen to us—so our experiences and world-views are all utterly different, but being alone within a unique point of view is, paradoxically, universal. I think the most idiosyncratic art can be the most far-reaching because it lets us see the world through someone else’s eyes.

|

Twinship, clay and mixed media on panel 18 x 24 x 10 inches, 2022 |

IM: In your reliefs, archetypal objects come into play as in a still-life assemblage. In the work “Twinship” a human-like head is faced with the unknown of its “mirror image.” How does the notion of psychology affect your work?

JE: Both of my parents are actually psychoanalysts, and my sister and partner are in training to become psychoanalysts, so I’m pretty steeped in it! The title “Twinship” actually refers to a concept from self psychology, a developmental need to identify with someone to form our sense of self. I’m interested in concepts like projection, and in the case of the reliefs, how we’re able to identify with objects that we read as human faces or bodies. I like that “Twinship” and other pieces in the show feel open-ended. Viewers can bring their own stories and meaning to the work.

|

Strata, clay and mixed media on panel 27 x 18 x 6 inches, 2022 |

|

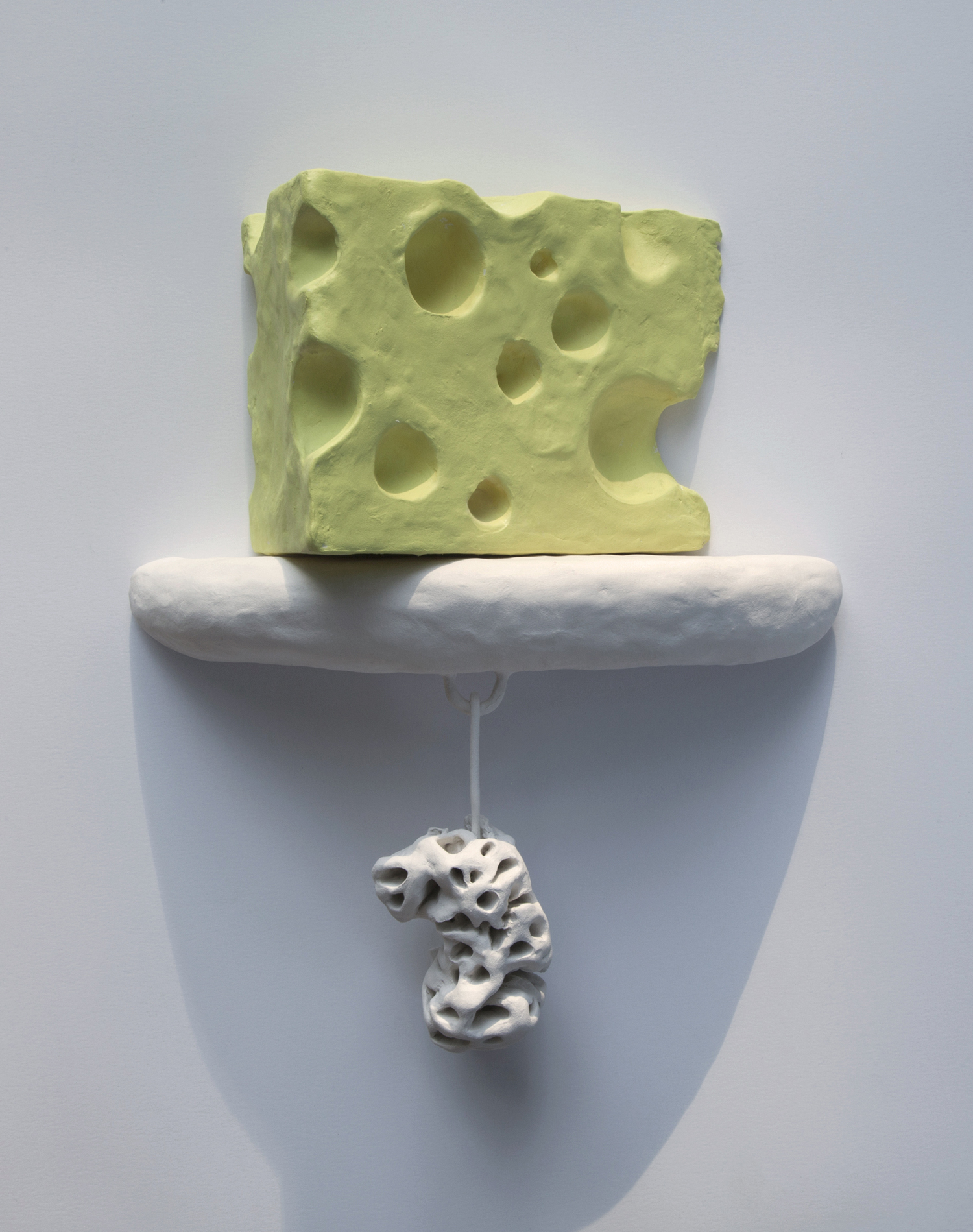

Normal Force, clay and mixed media on panel 24 x 18 x 9 inches, 2022 |

IM: The subtle colors that “bleed” through white – such as in Strata and Normal Force – are breaking in another manner the serenity of the seemingly white monochrome objects. The work touches painterly nuances with a tactile sensitivity. Can you talk about the forms that you are using, the making of the sculptures and their relation to your video work and painting?

JE: The reliefs are built from a range of smaller sculptures. I created some of them to scan and work with in 3D digital space and others to serve as props in live action videos. I also made new elements specifically for this work. In some of the pieces you mentioned, I covered painted sculptures with clay, but wasn’t too fussy about my process so some of the paint shows through, hinting at the earlier life of the objects underneath. My work has really evolved over decades, kind of following an art history timeline. I started as a painter, then began making videos that used painted sets, live actors, and in-camera special effects—techniques similar to the ones used by Georges Méliès and other early filmmakers.

For those videos, I handmade every on-screen element: backgrounds, miniatures, props, and masks for actors. They were rough looking and clearly artificial, but specific enough that viewers might project their own emotions onto the masks and imagine that the spaces continue beyond the edges of the video frame.

Eventually I incorporated newer techniques like 3D scans, digital imagery, and motion capture. In these later works, I liked to play the inhuman algorithm against human touch, movement and emotion. Now, with this show, I’m back to simple, handmade objects that suggest all of those earlier stages. The reliefs feel like they’re about world-building too, just in a more stripped-down way.

|

Quiver, clay and mixed media 27 x 20 x 3 inches, 2022 |

IM: What is the target of your arrow?

JE: A few years ago, I created a series of 3D-modeled, digital images that feature scans of clay arrows hovering mid-flight. I liked that these arrows function both as tactile objects and abstract symbols and that viewers could toggle between those two readings.

The arrows were also a visual joke about the absence of gravity in digital space, and a reflection of my obsession with this completely airless, timeless quality in Piero Della Francesca’s paintings.

A few years ago, I was watching physicist Brian Greene’s Fabric of the Cosmos. He was explaining the “arrow of time.” If I’m remembering this right, it’s the idea that time only moves in one direction because of entropy—as time moves forward, entropy increases: a glass jar shatters as time moves forward, but to move backward, all those shards would have to return to their starting positions, which is pretty improbable.

Greene asks what would happen if time wasn’t bound to entropy. Could we reverse it? I like thinking about the arrow in the current show in that way. It’s a very insistent object, but maybe it just seems that way because our experience limits our imagination of what’s possible.

IM: Thank you, Jonathan.

JE: Thanks Irini—it’s been a pleasure!

|

| The Capital of Fine is OK, Installation View, Essex Flowers, New York |

|

| The Capital of Fine is OK, Installation View, Essex Flowers, New York |

|

| The Capital of Fine is OK, Installation View, Essex Flowers, New York |

|

Choppers, clay and mixed media on panel 24 x 18 x 6 inches, 2022 |

|

Blocks, clay and mixed media 15 x 13 x 6 inches, 2022 |

|

Soft Shoe, clay and mixed media on panel 44 x 21 x 8 inches |

Jonathan Ehrenberg’s work has been included in exhibitions at MoMA PS1, SculptureCenter, The Drawing Center, Nicelle Beauchene Gallery (New York), Futura Center (Prague), The B3 Biennial (Frankfurt), Temnikova & Kasela (Tallinn), and Nara Roesler (São Paulo). He has participated in residencies at LMCC Workspace, Harvestworks, Skowhegan, Triangle, The Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, and Glenfiddich in Scotland, and his work has been reviewed in publications including The New York Times, The New Yorker, and Art in America. He received a BA from Brown University, and an MFA from Yale, and teaches at Lehman College, CUNY. He was born in New York, NY, where he currently lives and works.

Irini Miga’s practice traverses sculpture, installation, notions of drawing, text and performativity. Recent solo exhibitions include: An Interval at Flyweight Projects in New York (2020); Away is Another Way of Saying Here, at Essex Flowers gallery, in New York (2019); and Reflections, at Atlanta Contemporary Museum (2018). Her work has been included in group exhibitions such as Going Viral at Steinzeit gallery in Berlin (2022); Spring Works, Summer Shows, at Haus N Athen in Athens (2021); Mr. Robinson Crusoe Stayed Home at Benaki Museum in Athens (2021); Room for Failure at Piero Atchugarry gallery in Miami (2019); Tomorrow’s Dream, at Neuer Essener Kunstverein in Essen (2018); When You Were Bloom, Thierry Goldberg Gallery in New York (2018); Scraggly Beard Grandpa, at Capsule Shanghai, in China (2017); Marginalia, at The Drawing Center in New York (2017); The Equilibrists, organized by the New Museum in New York, the DESTE Foundation and shown in the Benaki Museum in Athens (2016). She has been honored residencies by several organizations including the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture; Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, Workspace Program;The Fountainhead Residency; The Watermill Center; Bemis Center for Contemporary Art Residency Program and more. Her practice has been mentioned at Artforum, Flash Art, Time Out New York, Ocula, Blouin ArtInfo, Huffington Post, Art F City, and ARTnews. Irini Miiga studied art at London’s Central Saint Martins College, earned a BFA from the Athens School of Fine Arts in 2005, and an MFA in Visual Arts from Columbia University, New York on a Fulbright Grant. She was born and raised in Larissa, Greece. Currently she lives and works between Athens and New York (US).

*Source: Jonathan Ehrenberg’s “The Capital of Fine is OK” - Press Release